Surface Waters

Surface waters are prominent landscape features that have often determined both the location and form of regional settlement. Surface waters include lakes and ponds (both natural and impounded), rivers and streams (permanent and intermittent), vernal pools, and wetlands (see Water Resources Map). The region's abundant surface waters are critical for sustaining ecological systems and provide numerous valuable resources.

RIVER BASINS AND WATERSHEDS

The majority of the Windham Region is located within the Connecticut River Basin with small portions located in the Hudson River and Lake Champlain Basins. These basins contain many rivers and tributaries, each with their own unique watersheds. Table 5-1 shows the Windham Region’s major watersheds and their respective acreage. A map of the major river basins is available in the map section, Basins and Watersheds Map, Basins and Watersheds Map.

Table 5-1: Windham Region Watersheds

| Watershed | State Watershed Basin Number | Acreage in Region | Percent of Region |

|---|---|---|---|

| Connecticut River Basin | 582,598 | 99.0% | |

| West, Williams and Saxtons Rivers | 11 | 306,150 | 52.0% |

| Deerfield River | 12 | 172,221 | 29.0% |

| Lower Connecticut River | Now incorporated into Basins 11 and 12 | 104,237 | 18.0% |

| Lake Champlain Basin | 660 | 0.1% | |

| Otter Creek | 3 | 660 | 0.1% |

| Hudson River Basin | 6,630 | 1.0% | |

| Batten Kill | 1 | 6,630 | 1.0% |

| Total | 589,888 | 100.0% |

Source: Windham Regional Commission GIS Department

LAKES AND PONDS

Within the watersheds of the Windham Region, there are 33 lakes and ponds over 20 acres in area. These water bodies provide their own special habitats and recreational opportunities, as well as conservation and water quality issues. Some of the issues particularly pertinent to lakes and ponds are exotic invasive species such as Eurasian watermilfoil, competing recreational uses, dam management, and extraction of water for snowmaking and other commercial uses.

The Vermont Watershed Management Division’s Lakes and Ponds Section developed the Lake Score Card to provide a method for conveying the large amount of data gathered through their monitoring efforts. The Score Card rates Vermont lakes in terms of water quality, aquatic invasive species, atmospheric pollution, and shoreland and lake habitat. Most of the lakes within the Windham Region are in good condition for water quality and invasive species parameters. The region has many lakes who score in fair condition for mercury pollution, which comes from atmospheric deposition.

RIVERS AND STREAMS

Rivers and streams are dynamic systems that are constantly shifting in response to streamflow and ecological conditions making them complicated to understand. As a result, thorough study is required to understand how different sections of a stream relate to each other. Rivers and streams are critical waterways that provide vital breeding, resting, and feeding areas for fish, birds, and other wildlife species as well as critical habitat for plants, including rare, threatened, and endangered species. Rivers and streams provide water for drinking and domestic use, for generating electricity, for powering machinery, for irrigating crops, and for transporting goods. They enhance the beauty of the landscape and the quality of scenic and recreational experiences in the region. Healthy rivers and streams also provide vital ecological services such as helping to purify water, transport water and nutrients through the region, and moderate floods and droughts.

Undeveloped and undisturbed land along rivers and streams (riparian buffers) and along the shores of lakes and ponds (lacustrine buffers) are important for a number of reasons. They provide water quality values in terms of shade (temperature), pollutant filtration, and bank stability. They also provide habitat values both in the water, including direct sources of food and shelter for fish, and on shore, including viable habitat for plants and feeding, foraging, and travel corridors for wildlife. Finally, undeveloped waters shorelines provide a direct benefit to society in terms of scenery, recreation, and in many cases, buffering of flood waters.

FLOODPLAINS

Floodplains are lowlands along rivers, streams, and lakes that periodically become inundated with water during periods of high rainfall or spring runoff. They are important to the healthy functioning of river systems for retaining and infiltrating waters that might cause damage or destruction downstream. Floodplains are often the best agricultural lands because of their thick glacial deposits, minimum slope and proximity to surface water. Floodways are stream channels and adjacent floodplain areas that carry the bulk and force of the river’s flow, and must be kept free of encroachment.

Nearly three-quarters of Vermont streams have become disconnected from their historic floodplains through human impacted changes to the landscape. A stream’s lack of access to its floodplain, including many wetland areas, creates an unstable condition in which the stream no longer has its “release valve” or ability to dissipate energy out of the stream channel and onto the surrounding landscape. Excessive streambank erosion, depositing of sediments, fast moving floodwaters, and increased damage to infrastructure and vulnerable development are all potential outcomes of a stream or river that has lost connection with its floodplain.[1]

RIVER CORRIDORS

Fluvial (or river-related) erosion refers to major streambed and stream bank erosion associated with the often-catastrophic physical adjustment of stream channel dimensions (width and depth) and location that can occur during flooding. Fluvial erosion becomes a hazard when the stream channel that is undergoing adjustment due to its instability, threatens public infrastructure, houses, businesses, and other private investments. The mapped area subject to fluvial erosion risk is called the river corridor.

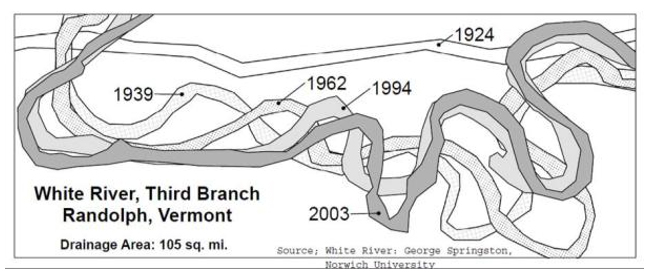

Rivers and streams are not static in the landscape. The shape of a river channel, including its width, depth, pattern, and slope, changes over time due to the action of water, sediment, and debris from the surrounding watershed as shown in the example (Figure 5-5). Rivers in “dynamic equilibrium” carry water, sediment, and debris, even during high water, without changes occurring in the depth, width, length, or slope of the channel. The channel may move and shift position within the landscape, but these other factors remain relatively constant. Human development, especially within river corridors, that significantly alters the runoff pattern of water and sediment can disrupt the equilibrium of a river system. When development changes the relationship of the river with its floodplain or constrains the river from maintaining or re-establishing equilibrium conditions, the result is often costly losses due to erosion. This erosion can also contribute to increased sediment and nutrients that can compromise water quality and aquatic habitat.

FIGURE 5-5: WHITE RIVER CHANNEL OVER TIME

Source: Agency of Natural Resources DEC Watershed Management Division

The degree of adjustment that streams will go through to establish and maintain equilibrium (having a dimension, pattern, and profile where erosion is minimized) is significant and a changing landscape makes finding that equilibrium more difficult. It is not safe or environmentally sound to encroach within a river corridor, as these areas are naturally unpredictable and are changing to seek equilibrium. Consideration of stream geomorphology and long-term river dynamics in land-use decision-making can protect and restore water quality and habitats, and mitigate damages and economic losses incurred as a result of floods and fluvial erosion.

FLOOD RESILIENCY

The Windham Region is vulnerable to the destructive impacts of the region’s surface waters as we are reminded on an increasingly frequent basis. Although flooding is common in the Region, the severity of both Tropical Storm Irene in 2011 and the flooding of July 2023 raised considerable public awareness and community discussions about the need to address flood resiliency. Resiliency is the ability of a community to respond and adapt to natural and human-caused disasters. Potential flood damage in this region is exacerbated by a combination of frequent intense storm events and traditional settlement patterns which historically placed road networks, villages, and other development along river and stream corridors, often within the floodplain and river corridor.

Flooding is a natural ecological process. While river and stream channels serve to convey water downstream, floodplains and wetlands are critical for the infiltration and temporary storage of water during large storm events, thereby reducing peak flows and mitigating flooding downstream. Each of these ecosystems fulfills critical functions that have significant downstream benefits and thus should be preserved to the greatest extent possible. Experience has repeatedly demonstrated that development in floodplains and river corridors, and especially in floodways, is inherently dangerous, due both to the immediate hazards associated with flood water inundation and to the increased flooding that may occur downstream when developed floodplains are no longer capable of retaining flood waters. Such development can also interfere with the function and quality of waterways, floodplains, and wetlands. While engineering techniques may help to mitigate the consequences of flooding on development within floodplains and river corridors, the fact that development can take place in these areas does not mean that development should occur in these areas. Development in river and stream corridors fundamentally places life and property at risk, and may exacerbate problems downstream. Towns are encouraged to develop policies and regulatory and non-regulatory local strategies to protect floodplains and river corridors.

There are many tools available to the region and towns for assessing their waterways and for promoting development that will allow existing waterways and future development to co-exist in a manner respectful of each other’s needs. These tools include Stream Geomorphic Assessments, River Corridor Plans, Stormwater Master Plans, and Bridge and Culvert assessments. The Vermont Watershed Management Division has multiple guidance documents and reports available to towns and groups interested in pursuing this type of assessment.

NATIONAL FLOOD INSURANCE PROGRAM

Under the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), the Federal Emergency Management Agency makes insurance available to property owners in communities that implement and enforce zoning bylaws that meet standards to reduce future flood risk to new development and improvements to existing development. A major purpose of the NFIP is to alert communities to the danger of flooding and to reduce flood related property damage. The only option for property owners seeking flood insurance in a community that does not participate in the NFIP is to purchase it through the private insurance market, which can be more costly.

Special Flood Hazard Areas (SFHAs) are officially designated on Federal Insurance Rate Maps (FIRMs), prepared and published by the Federal Emergency Management Agency. The current FIRMs in Vermont are dated and map updates are a digitization of old data; therefore, in many instances SFHAs do not reflect the realistic extent of flood prone areas. For this reason, and to more accurately and adequately regulate the risk, communities should regulate both the SFHA and the river corridor. Communities can also adopt more stringent standards than the minimum measures acceptable for NFIP participation as a way to lessen the gap between the older map data and the true risk. As well, property owners that have built structures that may be subject to flooding or fluvial erosion are able to purchase flood insurance regardless if they are located in a mapped flood hazard area or not.

VERNAL POOLS

Vernal pools are small wetlands resulting from the persistence of standing water for a portion of the year, characterized by a lack of vegetation, though they may support some herbaceous wetland species. Vernal pools are perhaps best known as important breeding habitat for amphibians. Typical Vermont species that rely on vernal pools for reproduction include the Spotted Salamander, Blue-spotted Salamander, the Jefferson Salamander, the Eastern Four-toed Salamander, and the Wood Frog. Other animals use pools as well, such as fairy shrimp, fingernail clams, snails, eastern newts, green frogs, American toads, spring peepers, and a diversity of aquatic insects. The Vermont Center for Ecostudies hosts an on-line interactive database of vernal pools in the state in the Vermont Vernal Pool Atlas.

Vernal pools and the organisms that depend on them are threatened by activities that alter pool hydrology and substrate, as well as by significant alteration of the surrounding forest. Construction of roads and other development in the upland forests around vernal pools can negatively affect salamander migration and mortality. Adjacent timber harvesting can have significant effects on vernal pools, including alteration of the vernal pool depression, changes in the amount of sunlight, leaf fall, and coarse woody debris in the pool, and disruption of amphibian migration routes by the creation of deep ruts.

WETLANDS

The region's wetlands are vital for their role in recharging groundwater, regulating and filtering surface water flow, storing water, mitigating floods, and providing significant aquatic and wildlife habitat. For example, several Windham Region wetlands are host to a federally listed endangered plant species, the northeastern bulrush. Consequently, they require careful protection. The Vermont Agency of Natural Resource’s Natural Resources Atlas provides an inventory map showing Class I and Class II wetlands. There are currently no Class I wetlands in the Windham Region. New to the Natural Resources Atlas are the results from wetland health monitoring. This is a growing area of monitoring, but at this time only wetlands that have been reported as having some level of concern have been monitored.

WATER QUALITY

The surface waters of the Windham Region are monitored by both the State of Vermont and non-profit entities in the area. The 2022-2023 Water Quality Monitoring and Assessment Summary Report shows the majority of surface waters in the Windham Region to be in good condition. The Vermont Integrated Watershed Information System hosts an on-line data portal for water quality information. The Connecticut River Conservancy (CRC), and the Deerfield River Watershed Alliance in conjunction with the CRC, conduct water quality monitoring along several streams throughout the region. Information from their water monitoring efforts can be found on the Is it Clean? website.

Based on the results of the Vermont Lake Score Card the most common issue found in lakes and ponds in the Windham Region is atmospheric pollution. The most common pollutants for this region are acid and sediment, and the most common use impaired is aquatic life support. The sources of pollution identified as causing the greatest stresses on the region’s rivers and streams are:

- Streambank erosion and de-stabilization

- Agricultural land uses and activities

- Removal of riparian vegetation from streambanks

- Developed land and road stormwater runoff

- Flow alteration from hydroelectric facilities

- Snowmaking water withdrawals to support ski resort operations

- Channel instability and confined streams

Riparian buffers are important for mitigating many of these pollution sources, preventing them from entering surface waters.

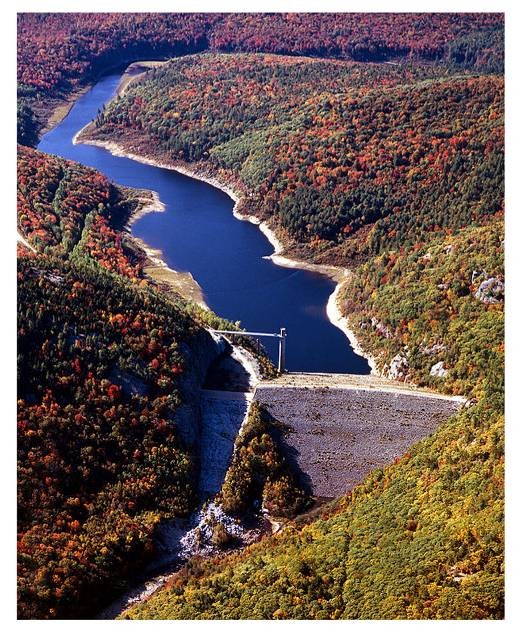

DAMS

Digital Visual Library

There are numerous dams of various sizes constructed on streams and rivers in the Windham Region. They provide a variety of benefits including power generation, flood control, and recreational opportunities, such as swimming and boating. However, these structures can have significant negative environmental impacts, contributing to stream siltation, altered water levels and flow fluctuations, increased water temperature, decreased dissolved oxygen, and impeded fish passage.

Dams used for power generation impact rivers in many ways beyond those listed above. Storage and release cycles of water for generating power need to be monitored to ensure aquatic habitats are not adversely impacted, generator turbines must be situated and designed to minimize damage to passing fish and storage capacities of dams holding water for future release, and power generation must be monitored to ensure dam structural safety.

Dams whose removal might provide substantial or unique environmental restoration potential, or that produce very little in terms of cost-effective renewable energy, might be candidates for removal. The removal decision must be made with consideration of the benefits derived, as well as the costs of removal and, if an energy generation facility, for replacement power that would be passed on to power companies and consumers. Evaluation on a case-by-case basis, use of appropriate guidelines and agreement on a replacement value is important. The Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation Dam Safety Program administers the State Dam Safety Rule, manages the Vermont Dam Inventory (VDI) database, oversees a permit program for construction and alteration of dams, an inspection program, and an annual registration program.

MANAGEMENT OF SURFACE WATER RESOURCES

Improved watershed management and cooperation among towns, state, and federal agencies, and area residents, will be required to meet competing uses of the region’s rivers, lakes, and ponds. There are several plans and assessments that help with the management of surface waters. These include Tactical Basin Plans, Stormwater Master Plans, Stream Geomorphic Assessments, River Corridor Management Plans, and Stream Classification.

Vermont’s Tactical Basin Planning process develops management plans for the waters of the state. The goal of the Tactical Basin Plan is to provide a roadmap for achieving watershed health. In the Windham Region, the two primary Basins are Basin 12, for the watersheds drained by the Deerfield, Green, and North Rivers, and several Connecticut River direct tributaries, and Basin 11, for the West, Williams, and Saxtons Rivers, and several Connecticut River direct tributaries. The basin planning process is on a five-year update cycle.

Stormwater Management Plans (SWMP’s) are developed for municipalities to identify runoff from infrastructure and what can be done to mitigate the hazardous effects of the runoff before surface waters become impaired. The Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation(DEC) maintains a list of communities that currently have SWMP’s. At the start of 2024, Brattleboro is the only town in the Windham Region with a Stormwater Master Plan and Londonderry, Wilmington, and the Greater Bellows Falls Area have SWMP’s in progress.

Stream Geomorphic Assessments examine and address the condition of a river system. The River Corridor Management Plan then provides recommendations of projects that will help improve the aquatic environment, such as river corridor protection, restoration projects, and hazard mitigation. DEC maintains a list of all Stream Geomorphic Assessments and River Corridor Plans conducted throughout the State.

All surface waters in the state are divided into four possible classes based on water quality: B(2) – good; B(1) very good; A(2) public water source; and A(1) excellent. All waters at or below 2,500 feet are designated Class B(2) for all uses, unless specifically designated as Class A(1), A(2), or B(1) for any use. All waters above 2,500 feet are designated Class A(1) for all uses, unless specifically designated Class A(2) for use as a public water source. All waters must continue to meet the criteria for their class, otherwise they are then listed as impaired, and a restoration plan must be developed and implemented. There are many surface waters below 2,500 feet that achieve a very high level of water quality. There is an effort to reclassify some of these waters to an A(1) status. Recommendations for reclassification are listed in the Tactical Basin Plans.

Efforts should be made to protect all surface water in the region (lakes, ponds, streams, vernal pools, wetlands) by maintaining their riparian zone in an undisturbed (or minimally disturbed) vegetated state, preferably in woodland, the recommended width depending upon various factors. When area for this type of protection is not available, such as in downtown areas, other best management practices (BMPs) should be implemented to slow the rate of runoff from a site, such as through the use of minimized development footprints, bioswales, or green roofs. Of special concern is the West River watershed, including the Rock River, Winhall Brook and Wardsboro Brook, which see a high rate of bank failures and are hazardous to infrastructure.

[1] Friends of the Winooski River, Living in Harmony with Streams: A Citizen’s Handbook to How Streams Work